By James Kwantes

Resource Opportunities

Fremont Gold is a Resource Opportunities sponsor company.

“Hello, you’ve reached Rock Bottom.”

It was the greeting for those calling Mongo’s Rock Bottom Cafe, the popular expat bar opened by exploration geologist Dennis “Mongo” Moore and a partner in La Paz, Bolivia. That was in the early 1990s, before Bolivia became a rather unfriendly place to explore for mineral deposits. At the time, the country was a thriving centre for mineral exploration. And Mongo’s, in Bolivia’s capital city, was a gathering place for geologists and drillers from around the world.

It’s a curious name for a bar in a city situated 3,600 metres above sea level. But it may make perfect sense given the description of geology as “liquor and guessing” — immortalized in a Dilbert comic strip — combined with a sector in which gloomy lows are the companion to occasional euphoric highs.

These days, Moore is president of Fremont Gold (FRE-V), a Nevada-focused exploration company focused on new discoveries and drilling for gold on the doorstep of McEwen Mining’s (MUX-T) Gold Bar mine in the Battle Mountain-Eureka-Cortez trend of northern Nevada.

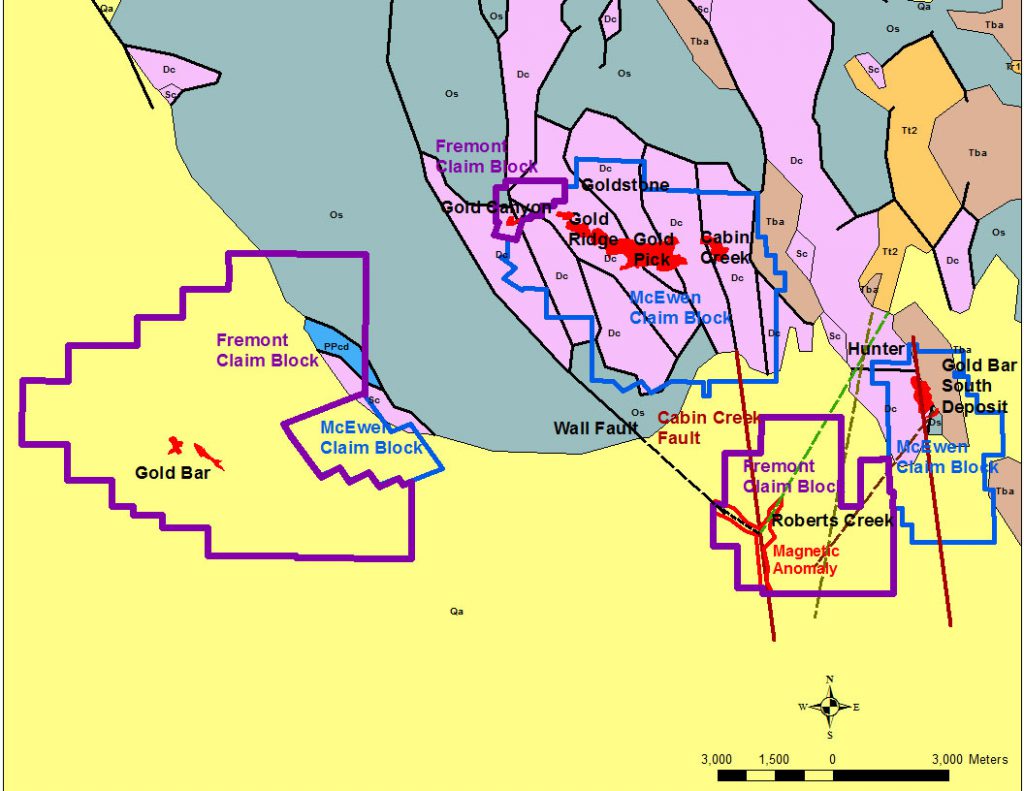

Fremont is on the eve of a 1,000-metre drill program at Gold Canyon, one of the satellite pits to the original Gold Bar mine. The other satellite pits are owned by McEwen Mining, which comprise McEwen’s Gold Bar mine — expected to begin production this quarter. Fremont recently cut short a drill program at the original Gold Bar after the first three holes failed to intersect significant mineralization.

The company will also undertake a discovery drill program this summer at its North Carlin project at the northern end of the Carlin trend. Drilling will target a gold and mercury soil anomaly that is coincident with a magnetic high. At least 1,000 metres of drilling is planned.

LOCKING UP LAND IN A TOP JURISDICTION

Last September, Fremont announced it had acquired the Roberts Creek claim block about a kilometre south of McEwen’s Gold Bar mine, taking its holdings in the neighbourhood to 5,348 hectares. Recently concluded magnetic and soil surveys revealed geophysical and geochemical anomalies at Roberts Creek that coincide with multiple faults, according to a Feb. 22 Fremont news release.

The company is more than a McEwen “closeology” play. Moore really likes the company’s North Carlin property, a package of three claim blocks directly on the northern end of the Carlin trend (about two km north of the Rossi mine). Fremont optioned one claim block from Ely Gold Royalties and staked the rest.

Moore is an Aussie-American who landed in Vancouver from the jungles of the Amazon and now makes his home in Lisbon, Portugal. He’s assembled a strong team at Fremont. Clay Newton, the VP Exploration, is a PhD structural geologist with decades of experience in Nevada and California. Last year, Fremont brought in Blaine Monaghan as CEO and director. Monaghan has raised more than $100 million for mining projects around the world and was most recently the VP Corporate Development for Allegiant Gold (AUAU-V), the Nevada-focused spinout of Columbus Gold (CGT-T).

As for Moore (right), the geologist has hit a few bottoms himself and bounced back — both before and after the Bolivian bar venture. He got a BSc in geology/earth sciences at the University of Oregon, where his love of exploration included mountaineering. Moore moved to Australia in 1981 and eventually joined the gold rush that was sweeping through the southwest Pacific (Australia was where he picked up the “Mongo” moniker). Working as a contract geologist based out of Australia, Moore got his first taste of jungle exploration in Papua New Guinea. Those were early days for mineral exploration in PNG. On one expedition, Moore encountered a group of local children who fled in fear because they had never seen a white man with blue eyes. Moore got malaria twice.

As for Moore (right), the geologist has hit a few bottoms himself and bounced back — both before and after the Bolivian bar venture. He got a BSc in geology/earth sciences at the University of Oregon, where his love of exploration included mountaineering. Moore moved to Australia in 1981 and eventually joined the gold rush that was sweeping through the southwest Pacific (Australia was where he picked up the “Mongo” moniker). Working as a contract geologist based out of Australia, Moore got his first taste of jungle exploration in Papua New Guinea. Those were early days for mineral exploration in PNG. On one expedition, Moore encountered a group of local children who fled in fear because they had never seen a white man with blue eyes. Moore got malaria twice.

His Australia stint coincided with one of mining’s cyclical slowdowns, and Moore obtained a master of environmental engineering from the University of Sydney. What followed was an unsatisfactory foray into environmental engineering — and commuting through heavy Sydney traffic to an office job. That experience and a divorce left Moore itching to return to his first love: exploration. Opportunity knocked when Moore was contacted by David O’Connor, Ross Beaty’s Latin American business partner, who was looking for Spanish-speaking exploration geologists in Bolivia. Moore knew O’Connor from a one-year stint in Fiji, and the geologist was soon en route to Latin America.

FRIENDS IN LOW PLACES ON A LONELY PLANET

Moore landed in La Paz in October 1993 and quickly connected with the large expat geo community, usually over drinks. With only one decent bar in downtown La Paz, a French cafe, “We said, why don’t we open up our own geo-expat bar,” Moore recalled. He and a partner did, and the following year, Mongo’s opened (with the heavy lifting done by Moore’s new girlfriend Sherene, now his wife of 25 years). The bar soon became a centre for both gringo and Bolivian geologists and later, tourists.

Moore’s new home rekindled his interest in mountain climbing; he and friends used to tackle 6,500-metre mountains in multi-day treks. One of the mountains they climbed was Ancohuma (near Illampu), a 6,427-metre peak north of La Paz. After descending Ancohuma, Moore met Sherene at a hotel in the little town of Sorata. She was drinking tea with a female companion, and Moore — exhausted and sunburned after a fantastic but draining experience — was eager to return to La Paz for a celebratory dinner with his climbing companions.

“I said to Sherene, ‘come on, let’s head back to La Paz,’ Moore recalled.

“She said, ‘I’m drinking tea here, can’t we hang out for a bit.’ I said, ‘No, I want to get back before it gets too dark.’ ”

“The other woman looked at me like I was a cretin, and I kind of gave her a dirty look as well.”

“My wife reluctantly came along and she didn’t say a word until we were about 20 minutes down the road. She says, “Do you know who that was?”

I said, “No, and I don’t really give a shit.”

She says: “That’s the woman who writes the Lonely Planet guide for Bolivia,” Moore said with a laugh.

“When she finally came to visit the bar, I told her she had nice eyes, but of course she saw right through me.”

On the geological front, Moore went to work for Altoro Gold, a Ross Beaty company that was exploring for gold but later pivoted to platinum-palladium projects in Brazil. And it was in Brazil where Moore made his first big discovery, in 1996-97.

Northern Brazil was home to one of the world’s largest gold rushes in the 1980s and 90s, with more than 1 million people flocking to the region. The easy gold was largely gone by the time Moore arrived in late 1996, although he immediately heard about golden riches being unearthed in the “wild west of the Amazonian jungle.” One of the main centres of Amazonian gold production is the Tapajos river system, a major tributary of the Amazon in Para state. The system has produced an estimated 25 to 50 million ounces of gold over the past 50 years, making it the third-largest alluvial field in the world. At the time there was not a single industrial-scale gold mine in the region (even now there is only Serabi Gold’s 40,000-oz/yr Palito mine).

THE DAY THAT CHANGED MOORE’S LIFE

In mid-1997 Moore spent five weeks flying around in 30-year-old Cessnas visiting the major “garimpos” (artisanal mines) in the jungles of northern Brazil. He visited, sampled and photographed over 30 garimpos and ranked the 20 best prospects.

Moore’s No. 1 prospect was Tocantinzinho, a small hill with two pits on either side being worked by over 1,000 garimpeiros. It was one of his last stops. “As soon as I saw it, I thought holy shit, this looks good.” He took several channel samples on Aug. 23, 1997, an auspicious date — it was his daughter’s 10th birthday. The characteristics that stood out included the width of the stockwork veining in the saprolite and the number of garimpeiros working it.

“I was very excited about it and David (O’Connor) said, well let’s see how the numbers come up.” The two Tocantinzinho channel samples ran 36 metres at 2.68 g/t gold and 21 metres at 2.01 g/t.

“David came into my office and said, ‘I think you may have found a mine here.’ He was right, basically, and that changed my life.”

Altoro and the JV partner did a deal with the garimpeiros to secure the land package. The company used soil sampling to define a 400-m by 1-km gold-in-soil anomaly and did some auger drilling. However, the Bre-X scandal was in full bloom; in early 1998 Beaty fired virtually the entire Altoro gold exploration team (including Moore), eventually pulled the plug on Tocantinzinho and pivoted to platinum/palladium. Solitario later bought Altoro for the platinum/palladium project. Tocantinzinho was deemed expendable.

After a short solo motorcycle trip to southern Chile, Moore landed contract work in Peru with Barrick and later with Newmont before the work dried up completely. Moore relocated to New Jersey with his wife and again, tried a more conventional job in the environmental field. But he quickly tired of commuting two hours every day to a windowless brick building in a New Jersey industrial park and dealing with large corporate clients. One Sunday his wife was reading the New York Times and commented to Moore about an article on the rising gold price. The piece mentioned Minefinders, which was run by Mark Bailey — whom Moore had worked with in Bolivia. Moore reached out and was soon en route to Mexico. He went to work for Minefinders in the Sierra Madre of Mexico on a 9-month contract.

Over the years, Moore saw how the real money was made — he watched a friend strike out on his own, vend a copper project in northern Peru, and prosper. Inspired by the successful venture, Moore headed to Vancouver to try his luck and visited Alan Carter, who had been with RTZ in Bolivia and was at that time on the management path with BHP. They formed a partnership; Moore put out some feelers and discovered that Tocantinzinho was available from the original garimpeiro owners, whom he knew.

RE-SECURING TOCANTINZINHO

In early 2003, working from an Internet cafe in San Miguel de Allende, Moore negotiated a deal to option Tocantinzinho for $15,000 on signing. Three months later, he and Carter signed with a TSX-V junior for cash, shares and a hefty NSR. Moore sourced a drill and they began drilling 7 months later. The primary discovery hole was hole #4, which ran 170 metres at 1.72 g/t gold.

Exciting moments like this did not come along often. More often, it was small-town life in the jungle away from loved ones, not to mention missing the music, sports and culture of home. A celebration was in order — Moore and the day driller got drunk for three consecutive nights.

Retaining a valuable sliding-scale royalty was a sharp move for the business partners. In 2010, Eldorado Gold paid about $122 million to purchase Brazauro and the Tocantinzinho deposit, which now hosts about 2 million ounces at 1.42 g/t Au. Moore recently sold his share of the royalty for a tidy sum.

After 18 months managing Tocantinzinho, Moore and Carter formed Magellan Minerals and acquired the Cuiu Cuiu district 20 km northwest of Tocantinzinho. Cuiu Cuiu was arguably the largest garimpo in the Tapajos. Moore and a Brazilian partner had staked the area, which had produced more than 2 million ounces just from alluvials.

Moore spent the next 10 years living and working at Cuiu Cuiu and Itaituba, the nearest town which services the Tapajos region. Over the years he discovered about 1.5 million ounces of gold in three separate deposits. Cuiu Cuiu is now being advanced by Carter’s Cabral Gold (CBR-V), which has been finding higher-grade mineralization at the project. On February 28, Cabral announced an intercept of 3.4 metres grading 36.9 g/t gold. Moore is a Cabral director and a large shareholder; Carter is Fremont’s chairman and a large shareholder.

In the 1980s, Cuiu Cuiu was a Wild West boom town with no roads, a short airstrip, about 5,000 residents, a police force, more than 40 brothels, and killings every week. The Itaituba airport was one of the world’s busiest during that decade, with 300 takeoffs and landings daily and more than 1,100 flights on the single busiest day. Companies trying to acquire stakes in the area included majors such as Rio Tinto and Phelps Dodge and personalities including Eike Batista.

Moore and Carter secured the claims to Cuiu Cuiu by convincing the garimpeiros to come together in a coop, then negotiating a deal with them. It was a lengthy process that took most of 2005-2006 and had a successful outcome: “The powerful female garimpeira, Amerita, was the last holdout — I basically had to get down on my knees and beg her!” Moore recalled.

The first Cuiu Cuiu drill program in 2006 — while Moore and Carter’s company, Magellan Minerals, was still private — hit 131 metres of about 1 g/t gold. Magellan went public in early 2008 as the company drilled one of its best holes: 220 metres at 2.2 g/t Au. The share price jumped from a dollar to $2.20 on the news. Moore and Carter managed to keep Cuiu Cuiu when they sold Magellan in 2016 to Ross Beaty’s Anfield Nickel, which was more interested in Magellan’s Coringa gold deposit in the Alta Floresta district of Brazil. (Anfield subsequently sold the Coringa deposit to Serabi Gold; Anfield is now part of Beaty’s Equinox Gold.)

Back in Nevada, Moore sees Fremont Gold as a kind of double-barrelled play on gold exploration in one of the world’s most prolific districts. A small drill program at Gold Canyon (above) in the summer of 2018 saw Fremont hit 16.8 metres of 1.9 g/t Au and 18.3 metres of 1.1 g/t Au. The company hopes to build on that success in identifying further mineralization on McEwen Mining’s doorstep.

Moore is even more excited by the North Carlin properties that Fremont staked — and by the prospect of new discoveries in the western hemisphere’s most prolific gold belt: the Carlin trend. In a bear market that is disproportionately rewarding new discoveries and discovery plays, identifying a gold discovery in such a rich district would capture the market’s attention. Fremont is also on the lookout for a more advanced project, Moore said.

As for Mongo’s, the watering hole eventually made it into Lonely Planet and other popular travel guides. The bar was sold to Vancouverite Colin Little in 1997 but the popular establishment finally “hit rock-bottom” just last year when it closed its doors.

Fremont Gold (FRE-V)

Price: 0.11

Shares outstanding: 53 million (67.2 million fully diluted)

Market cap: $5.8 million

Disclosure: Fremont Gold is a Resource Opportunities sponsor company and James Kwantes owns Fremont Gold shares. This is not financial advice and all investors need to complete their own due diligence.

James Kwantes is the editor of Resource Opportunities, a subscriber supported junior mining investment publication. Mr. Kwantes has two decades of journalism experience and was the mining reporter at the Vancouver Sun. Twitter:

James Kwantes is the editor of Resource Opportunities, a subscriber supported junior mining investment publication. Mr. Kwantes has two decades of journalism experience and was the mining reporter at the Vancouver Sun. Twitter:  Resource Opportunities (R.O.) is an investment newsletter founded by geologist Lawrence Roulston in 1998. The publication focuses on identifying early stage mining and energy companies with the potential for outsized returns, and the R.O. team has identified over 30 companies that went on to increase in value by at least 500%. Professional investors, corporate managers, brokers and retail investors subscribe to R.O. and receive a minimum of 20 issues per year. Twitter:

Resource Opportunities (R.O.) is an investment newsletter founded by geologist Lawrence Roulston in 1998. The publication focuses on identifying early stage mining and energy companies with the potential for outsized returns, and the R.O. team has identified over 30 companies that went on to increase in value by at least 500%. Professional investors, corporate managers, brokers and retail investors subscribe to R.O. and receive a minimum of 20 issues per year. Twitter: